Openly sharing your work brings more attention to it, which is good, right? The answer, for me though, is often “it’s complicated.” This is what happened when I went to visit a giant tech company, in hopes for collaboration, but later found that they tried to patent some of my research instead!

Image by Leah Buechley

How it started

My work in electronic books started when I was still an undergrad, during a research internship where I made a pop-up book with lights and sensors in the pop-up elements. This was under the guidance of my advisor Leah Buechley.

Since that time I’ve fallen in love with paper and electronics and books and storytelling. And have since played with other ways to combine electronics with books, such as a sketchbook with a power supply for “sketching” in circuits. As well as trying to tell stories with interactivity, such as a storybook about an LED named Ellie, who dreams to be a star.

Rewind to March 24, 2014, during the second year of my PhD at the Media Lab. I was invited to visit Google ATAP (Advanced Technology and Projects) to learn about some of their new projects in storytelling. I got to visit their space, meet some of my creative heroes and I shared with them all of my work in interactive books and storytelling.

What started as just a visit quickly turned into a job interview. I was even invited to share my work directly with Regina Dugan, the director of ATAP at that time! I was excited, thinking perhaps I would be invited for a summer internship. It turned out they found my work so relevant that they offered me a job on the spot.

It was a tough choice: I was two years into my PhD and would’ve had to take a leave from the program to pursue this project. After asking many people, the advice was clear: stay in school. So I decided to turn down the offer and continue pursuing my PhD. That’s where the glitter ends.

They’re trying to patent electronic pop-up books

Two years later, in March 2016 I find out from some paper engineering friends that some of the same people who had interviewed me had also applied for patents on interactive pop-up books with electronics. These patents covered many of the same things that had been discussed, that I’d showed them, with no mention of my or many others’ work known in the field. I found out from a friend who followed a pop-up book blog— luckily someone there notice the applications and was also concerned that google was trying to patent such book technologies, so they publish a blog post about it.

Suddenly there was a possibility that a giant tech company might have a patent over technologies that we all wanted to develop and work on. My fellow paper geeks and I were pretty worried.

So what do we do?

Well mind you, I found out about this about three weeks after I found out about the LED stickers patent, a totally unrelated incident in which our crowdfunding campaign backer successfully patented our product. Normally I would’ve thought “oh there’s way too much prior art” and this patent can’t pass. But after seeing what happened to LED stickers, I couldn’t be so sure anymore.

That said, the fact that these two unrelated situations were happening to me simultaneously kind of made it all feel a bit absurd. And luckily, because I had experience from the first patent issue, I was able to be much more calm this time around!

1. Don’t panic.

Some of the best advice I ever got was to not let worry about legal matters distract you from what matters: doing your work. So after calming down, I…

2. Make a prior art list. I made a list of all of my own publications involving books and electronics: academic papers, blog posts, videos, media and press. I also included work from others—it doesn’t have to be your own work; anyone’s work will do for prior art!

3. Look up the patent application status on USPTO.gov Public PAIR.

4. Get legal help! Because these are not things to handle alone, especially if the patents are being filed by a giant company!

What we found

I looked up the patent application and luckily, this time the patent application was still being reviewed by the patent examiner. It had not issued! The provisional was filed August 29, 2014, months after my first interview and visit back in March 2014. Two of the inventors listed were the same people who had interviewed me.

So what did we do?

First, because it was still a patent application, we could still submit prior art to it. My friend and collaborator Akiba generously did just that by submitting my research paper directly onto the application page.

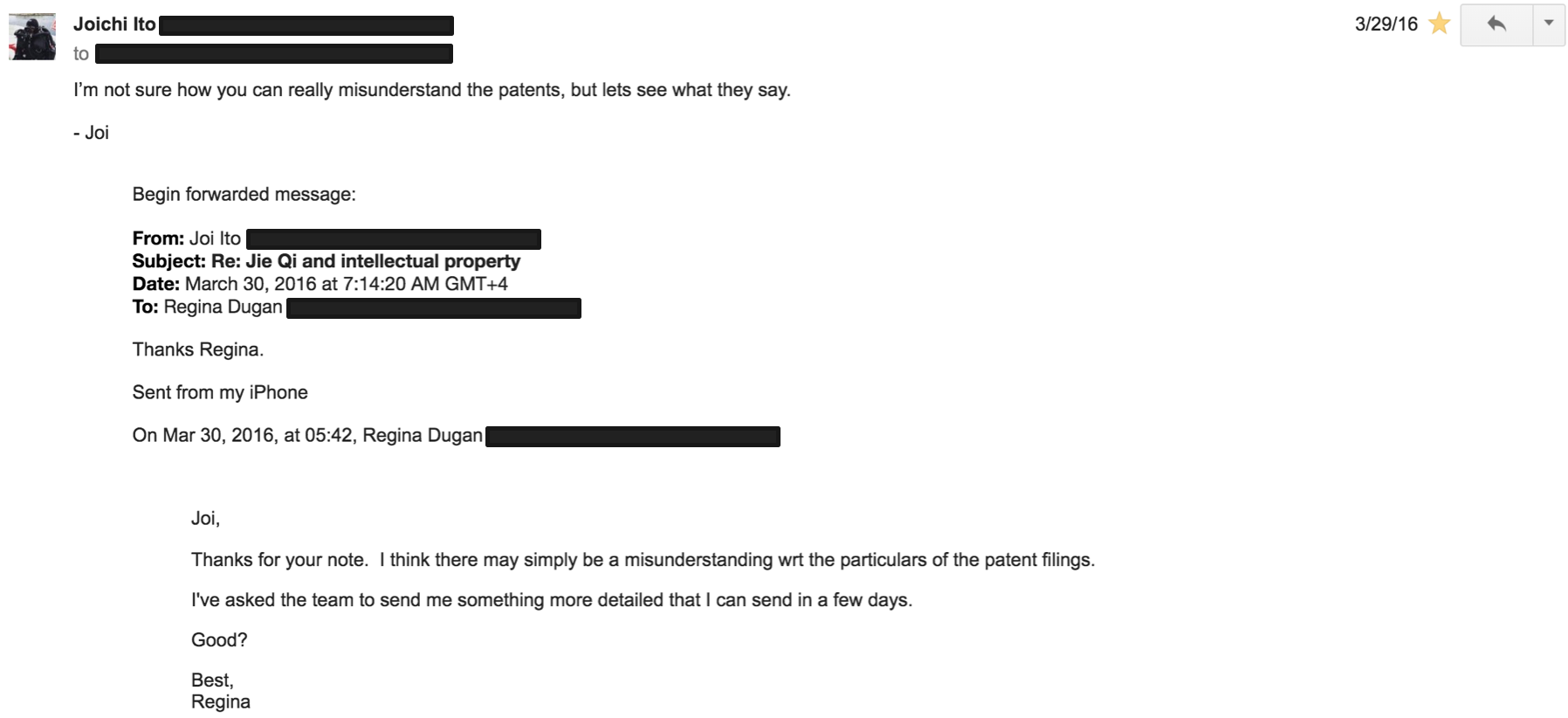

Second, and very luckily for me, the director of the Media Lab Joi Ito knew the director of ATAP at the time, Regina. He was able to get in touch with her directly and we were able to quickly schedule a chat to address the situation.

So we had a call directly with their team. As part of negotiations, they offered to add me as an inventor on the patent application if it meant the application could stand. I said no, because in order for me to be an inventor on they patent they would have to add all the other inventors who have contributed to blending books and electronics—I’m not the only one working on this!

What I didn’t realize at the time is that there’s actually a huge difference between inventor and assignee.

An inventor is the one credited with coming up with the idea for an invention. The assignee actually gets the legal rights to the patent. It’s a bit like how an architect (the “inventor”) may design a house but it’s the home owner (the “assignee”) that gets to live in it, and very often those aren’t the same people. It’s the same situation here: Google ATAP would’ve still owned the patent rights even if I got to be listed as an inventor. Meaning even though I would be on the patent and get credit for the work, I wouldn’t actually get rights to use the invention. Luckily I dodged that one, even though it was by accident!

Next the strange thing was that about a couple weeks into the conversation, Regina left Google ATAP. In the process, she put us directly in touch with ATAP’s senior council, who thankfully agreed to submit all of the prior art we had sent them to the USPTO as prior art for the patent application.

The patent application has since been rejected and abandoned, which means that for now the application is not being pursued as a patent. Even more good news: abandoned applications stay in the USPTO’s system, so it’s now prior art!

Good story, right?

In this case, I was incredibly lucky to have the support of a large institution (MIT) and even more lucky that we had a direct connection to ATAP through Joi to sort out the situation. I’m super grateful but realize that most other people in my position probably would not have had it so well. And I’m not sure what to tell them—unfortunately. Only that if one were trying to contact a large institution about patent issues, definitely do not go at it alone. Make sure to get a legal expert. Even in our navigating the patent issues with ATAP, we also always had the guidance of lawyers and legal experts.

What did I learn?

My biggest fear was that my fellow paper engineering friends and I would not be able to explore books and electronics further if these patents went through.

However, It turns out that at many large companies who have their own internal patent attorneys, it’s common for employees to get bonuses in the thousands of dollars for just sharing their work with the legal team or turning the disclosure into a patent application. There’s bigger bonuses if the patent issues.

I’ve learned that there are even lunch sessions at some big companies where people get to sit and chat with a patent lawyer to see if some patent could be drafted. If there’s a bonus attached, there’s even more incentive.

If students got the same bonuses for applying for patents, I can assure you there would be more patents coming from universities! What I mean is, it’s possible that sometimes people are less motivated by legal rights to a particular invention and more so by other incentives like getting financial bonuses, the validation and prestige of being a patent holder, or beefing up the patent statistics of a company for valuation purposes.

What about openly sharing work?

So in the end, unfortunately, I don’t have a perfect answer. Because on the one hand, sharing your work may lead to amazing collaborations with large companies that have the types of resources and expertise to get amazing, imagination-filled projects off the ground.

However, you may also run the risk of having work being patented away. In this case of electronic pop-up books, it appears that the people on the team have since stopped working on the project and the outside world wont know whatever became of it. The good news, though, is that since the patents never went through, the project itself is still open for exploration. Meaning anyone can still continue innovating on electronic pop-up books without worrying about these patents!

Personally, I like to err on the side of sharing more. At the end of the day, it was my research papers and the published work of others that stopped the patent applications in their tracks. While sharing stuff out means more people see them, it also means there’s more prior art to draw upon to keep an idea open.

More importantly, sharing work publicly keeps the project can alive and inspires others to continue developing!

Author: Jie Qi (Berkman Klein Center, MIT Media Lab)

Published: November 29, 2018